A Study in Scarlet may not be the favorite Holmes story of most Sherlockians, but the title is surely the one most played upon by authors. Consider:

- The first “BBC Sherlock” episode, broadcast on July 25, 2010, was A Study in Pink.

- Charlotte Holmes debuted in A Study in Charlotte.

- Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald” short story is a classic mash up of Sherlock Holmes and the Cthulhu Mythos, which Gaiman described as “Lovecraft/Holmes fan fiction.”

- A Study in Terror was the first film to have Holmes solve the Jack the Ripper murders.

- Michael Cox called his book about the Granada series with Jeremy Brett A Study in Celluloid.

- The first Klinger/King anthology was A Study in Sherlock.

- In the field of scholarship, Donald Redmond gave us A Study in Sources.

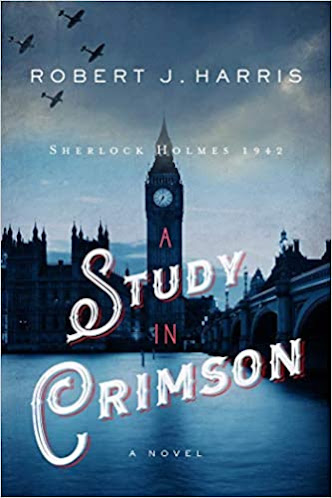

Now comes A Study in Crimson: Sherlock Holmes 1942 by Robert J. Harris, inspired by the Basil Rathbone movies—especially the first three, in which World War II plays such a large part.

In this re-imagining of the Baker Street saga, Holmes and Watson are in their 50s and met at Bart’s after the Great War. Watson was wounded by German guns, and Holmes was a spy. Now we’re in the middle of a second world war, and the Diogenes Club has been bombed.

The novel is a pastiche of the Universal films in ways that go beyond the timeframe. Holmes calls Watson “old fellow,” as he does in the movies but never in the stories. Mrs. Hudson is Scottish, like actress Mary Gordon, although Holmes said in “The Naval Treaty” that “she has as good an idea of breakfast as a Scotchwoman,” which implies she was not a Scotchwoman. The description of Lestrade matches actor Dennis Hoey, not the ferret-faced Inspector of the stories.

But the author notes in the afterword that the Watson of A Study in Crimson is not the bubus Britannicus portrayed by Nigel Bruce. And he certainly isn’t.

Although described by the publisher as a thriller, the

plotline is more of a whodunnit—and a good one. At Mycroft’s request, Holmes is

on the trail of a modern-day Ripper who calls himself Crimson Jack and is

duplicating—though not every detail—the crimes of the original madman. But this

one is not mad, and the reader can follow the clues to a satisfactory

conclusion.

If you are a stickler for canonical authenticity, this isn’t the book for you. Otherwise, hop on and enjoy the ride.

No comments:

Post a Comment